The First Time I Consider Ending My Life I Am Four

Published 2025

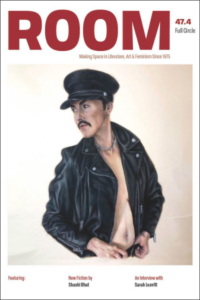

Room Magazine

We are allowed to take walks after dinner, my brother and me, leaving the table after folding our napkins and each saying, “May I be excused?” We explore the grounds of the resort, skipping along the concrete pathways winding between the tennis courts and walking slowly along the docks where yachts are tied up. My brother, five years older, looks at his glow-in-the-dark Timex every few minutes to decide when we have to go back.

We are allowed to take walks after dinner, my brother and me, leaving the table after folding our napkins and each saying, “May I be excused?” We explore the grounds of the resort, skipping along the concrete pathways winding between the tennis courts and walking slowly along the docks where yachts are tied up. My brother, five years older, looks at his glow-in-the-dark Timex every few minutes to decide when we have to go back.

This night I’m not excused to walk with my brother. I am only excused to go to the bathroom. I call it “ladies’ room” or I’m not allowed to go, so I pretend I’m a ventriloquist saying it, freezing my lips slightly ajar and altering my voice so the words seem like they’re coming from the saltshaker. I don’t go to the indoor bathroom next to the dining room though. Instead, I use the bathroom next to the pool that I watch lifeguards go in and out of during the day. On my way back to the dining room from the lifeguard bathroom I see my brother walking towards the tennis courts and quietly follow from behind so I can scare him. “BOO!” I yell, and he jumps and laughs and then chases me and I run. I duck behind a fat palm tree and hide there for a while, holding my breath.

My brother is better than me at almost everything but not at hide-and-seek or red-light green-light or kick-the-can or rope climbing. Even Leni admits I’m better at sports when I ask her during bath time, and she is super careful never to say anything unequal about my brother— even though she’s my nanny— so I know it’s the truth. If I hold my breath when hiding, my brother eventually gives up before finding me and yells “come out come out wherever you are” and I win. This night, after he yells “come out come out” and I reappear myself, I put my hands together and get down on my knees like we do in chapel and I beg for “one more time, one more time, one more time” and I don’t stop until he covers his eyes and counts.

I take off, running on the grass so my shoes don’t make noise on the cement pathway. I head for the Pro Shop which is closed at night and zoom up the stairs to the second level– an outdoor tented platform with heavy metal and vinyl chairs resort guests drag into different positions during the day to view tennis matches played on the courts below. No one ever drags their chairs back into place when they’re done, so at night it’s like a giant chess board abandoned right after the game ended. “Ready or not here I come!” shouts my brother, removing his hands from his eyes and walking around looking behind nearly every tree and bush, attempting to find me. From my perch I see he’s trying his hardest, like when he loses his bus pass before school and checks places it can’t possibly be like inside the piano, and I love him so much I want him to be better at things like this almost as much as I want to beat him. I watch the top of his head jerking in every direction. I try to use my mind like Mr. Spock in Star Trek, attempting to mess my brother’s hair— concentrating on dislodging the perfect side part he gets by holding a book on his head and tracing the spine of it with his comb— but it’s not working, his hair isn’t budging, and I give up. It’s now very dark out and I’m watching the face of my brother’s watch bounce around as he moves, like a magic glowing ball suspended in the night air. He wears the watch around the center of his cuff, on the outside of his shirt sleeve, which I know is an uncool way to wear it, but my brother doesn’t care about stuff like that; he never cares about dressing like the cool kids and he always presses his lips together in a tight smile when he moves his sleeve to tell the time, like he’s doing a really important job. Because there are short lamps shaped like mushrooms all along the path, I see the tops of my brother’s brown penny loafers shine every few steps when his feet step into their light, like someone on TV stepping into a spotlight to sing. I want so badly to have penny loafers. If I can get penny loafers, I want to put pesos into the slots instead of pennies, but my mother only says “maybe” to me having a pair, and it’s the version of “maybe” where she looks at the ceiling, so I don’t have a lot of hope.

I pretty much want everything my brother has and pretty much never get any of it. The boomerang, the plaid winter hat with the ear flaps that fold down, the microscope. If his watch breaks, he’ll be given a new one, and I’ve been promised the broken one. “Why do you want a watch that doesn’t tell time?” Leni asks me when I tell her this. “Since I can’t tell time it won’t matter” I say.

So this night, on vacation in Acapulco, while I’m playing hide-and-seek with my brother after dinner without permission, I suddenly hear my mother scream my brother’s name, “Jimmy!” and my brother immediately straightens like my GI Joe when I make him salute, and shouts “Yes!” My mother yells again, “Have you seen that sister of yours?!” and I see my brother’s head darting up and down and side to side to uncover where our mother’s voice is coming from. From my platform perch I see her smoke first, a gray cloud behind the tall hedges moving quickly forward like the smoke from a train chimney. I look over the railing— on tiptoes my head clears it— to the tennis court below, testing my arm strength by gripping the rail and pushing myself up gymnast-style until my elbows lock and I’m high enough to look straight down to the court below. If I want, I can get myself over it by leaning forward. If I want, I can definitely fall all the way down. Of course I know I won’t bounce like a tennis ball, or even like a racquet ricochets when the older kids get mad during their tennis lessons. I mean, obviously I know I’ll die, it will be over fast, like a slap, probably upon impact if I land headfirst like I’m not supposed to on the trampoline at school. I see my body lying there after, a jumble of me, blood oozing out slowly— like from squeezing a ketchup packet when the hole is too small— and puddling all around me as my mother, still smoking, looks down at me while stepping backwards so she doesn’t get blood on her shoes. Will my mother touch me, I wonder, to check if I have any life left in me? I decide she won’t. Instead, she’ll have my father lift me up and carry me… but to where? Where will my body be kept until the vacation is over and we go home to New York for my funeral?

That I don’t jump this night matters in two ways. The obvious way, but also something else: I think something that night I can never unthink. I don’t know if, during childhood, I think about dying more than other kids growing up in unhappy families, but after this night I retain the total and complete power to control one perfect thing in my life.

About

Awards

Columbia Journal: First Place Winner, 2020 Nonfiction Award for autobiographical essay “HYBRID”

Beyond Words Literary Magazine: Winner, 2020 Dream Challenge “Kaden has Covid”

The Maine Review: Hon. Mention, 2021 Embody Award for essay “HIDEOUS”

Sunspot Lit: Finalist, 2020 Inception Contest Flash Fiction “Before and After”

Streetlight Magazine: Hon. Mention, 2020 Essay Contest “Finding Barbie’s Shoes”

Gival Press: Finalist, Oscar Wilde Award 2021 for poem “Self-Portrait at Age 9 as Albert Cashier”

Craft Literary: Hon. Mention, 2021 Flash Fiction Award

North American Review: Finalist, 2020 Kurt Vonnegut Prize

Get in Touch

Recent Work

The First Time I Consider Ending My Life I Am Four – Room Magazine

The Day After Wikipedia Still Lists Her in Present Tense – The Southampton Review

The Name Dropper – The Maine Review

My Earliest Self is a Boy… – Electric Lit

T – The Rumpus

Denny and Me – Passengers Journal

Small-Town Nonsense – The East Hampton Star

A Conversation with Morgan Talty – The Rumpus

My Avatar (aka afab perpetrates heteronormative relationship) – Holy Gossip

What Goes Around – EAST Magazine

The Liar – The Normal School

I Drew a House – The Rumpus

More

HYBRID – Columbia Journal

Blended Family – The Southampton Review

There are No Baked Potato Chips in Palm Beach – Dash Literary Journal

Last Night I Dreamed My Mother Was Carl Reiner and I Was Sad She Died – Bangalore Review

Time Will Tell – The Fiddlehead (Excerpted from Winter 2023 Print Journal)

Parallel Family – Harvard Review

Finding Barbie’s Shoes – Streetlight Magazine

Deformed – RFD Magazine

#2486 – The Southampton Review

On Drinking – Stonecoast Review

My Last Dress – The Sun Magazine

Reviews and Interviews

Misperceptions, Assumptions, and Slurs: Jackie Domenus's No Offense – The Rumpus

A Conversation with Morgan Talty – The Rumpus

Naming Stars: An Interview with Andrés N. Ordorica – The Massachusetts Review

Interview by J Brooke of Hotel Cuba’s author Aaron Hamburger – Streetlight Magazine

J Brooke’s Reading Recommendations – The Fiddlehead

Two New Series Bravely Lose The Labels – Incluvie Film Review

Review of Melissa Febos’ Girlhood – Glint Journal

Review of Susan Conley’s Landslide – Streetlight Magazine

Interview with Massachusetts Review

Interview with Stonecoast Review

The First Time I Consider Ending My Life I Am Four

Published 2025

Room Magazine

We are allowed to take walks after dinner, my brother and me, leaving the table after folding our napkins and each saying, “May I be excused?” We explore the grounds of the resort, skipping along the concrete pathways winding between the tennis courts and walking slowly along the docks where yachts are tied up. My brother, five years older, looks at his glow-in-the-dark Timex every few minutes to decide when we have to go back.

This night I’m not excused to walk with my brother. I am only excused to go to the bathroom. I call it “ladies’ room” or I’m not allowed to go, so I pretend I’m a ventriloquist saying it, freezing my lips slightly ajar and altering my voice so the words seem like they’re coming from the saltshaker. I don’t go to the indoor bathroom next to the dining room though. Instead, I use the bathroom next to the pool that I watch lifeguards go in and out of during the day. On my way back to the dining room from the lifeguard bathroom I see my brother walking towards the tennis courts and quietly follow from behind so I can scare him. “BOO!” I yell, and he jumps and laughs and then chases me and I run. I duck behind a fat palm tree and hide there for a while, holding my breath.

My brother is better than me at almost everything but not at hide-and-seek or red-light green-light or kick-the-can or rope climbing. Even Leni admits I’m better at sports when I ask her during bath time, and she is super careful never to say anything unequal about my brother— even though she’s my nanny— so I know it’s the truth. If I hold my breath when hiding, my brother eventually gives up before finding me and yells “come out come out wherever you are” and I win. This night, after he yells “come out come out” and I reappear myself, I put my hands together and get down on my knees like we do in chapel and I beg for “one more time, one more time, one more time” and I don’t stop until he covers his eyes and counts.

I take off, running on the grass so my shoes don’t make noise on the cement pathway. I head for the Pro Shop which is closed at night and zoom up the stairs to the second level– an outdoor tented platform with heavy metal and vinyl chairs resort guests drag into different positions during the day to view tennis matches played on the courts below. No one ever drags their chairs back into place when they’re done, so at night it’s like a giant chess board abandoned right after the game ended. “Ready or not here I come!” shouts my brother, removing his hands from his eyes and walking around looking behind nearly every tree and bush, attempting to find me. From my perch I see he’s trying his hardest, like when he loses his bus pass before school and checks places it can’t possibly be like inside the piano, and I love him so much I want him to be better at things like this almost as much as I want to beat him. I watch the top of his head jerking in every direction. I try to use my mind like Mr. Spock in Star Trek, attempting to mess my brother’s hair— concentrating on dislodging the perfect side part he gets by holding a book on his head and tracing the spine of it with his comb— but it’s not working, his hair isn’t budging, and I give up. It’s now very dark out and I’m watching the face of my brother’s watch bounce around as he moves, like a magic glowing ball suspended in the night air. He wears the watch around the center of his cuff, on the outside of his shirt sleeve, which I know is an uncool way to wear it, but my brother doesn’t care about stuff like that; he never cares about dressing like the cool kids and he always presses his lips together in a tight smile when he moves his sleeve to tell the time, like he’s doing a really important job. Because there are short lamps shaped like mushrooms all along the path, I see the tops of my brother’s brown penny loafers shine every few steps when his feet step into their light, like someone on TV stepping into a spotlight to sing. I want so badly to have penny loafers. If I can get penny loafers, I want to put pesos into the slots instead of pennies, but my mother only says “maybe” to me having a pair, and it’s the version of “maybe” where she looks at the ceiling, so I don’t have a lot of hope.

I pretty much want everything my brother has and pretty much never get any of it. The boomerang, the plaid winter hat with the ear flaps that fold down, the microscope. If his watch breaks, he’ll be given a new one, and I’ve been promised the broken one. “Why do you want a watch that doesn’t tell time?” Leni asks me when I tell her this. “Since I can’t tell time it won’t matter” I say.

Mostly, I want to feel a watchband tight on my skin. I imagine the metal getting hot from the sun the way the top of my Coke can does when I leave it by the side of the pool to go swim. At the beginning of vacation, I’d taken a sip from my Coke after getting out of the pool and got burned, the hot can top leaving a red semi-circle extending above my upper lip, like someone tried drawing a fake smile on my face and missed my mouth. The fake smile was still there the next morning when I looked in the mirror while brushing my teeth, and at breakfast my mother said if it didn’t wear off by dinner time, she was putting some of her makeup on me to cover it up. I was desperate not to have her do that, but I didn’t say so because that would have made her do it for sure. I think if I get a watch, I’ll let the watchband get super-hot in the sun so it leaves a permanent mark on my skin that only I can see. I think it will be a tattoo like Popeye has. I don’t like how old-fashioned Popeye is, but I like tattoos and I like sailor uniforms, and I like humming the theme song— I’m Popeye the sailor man, I’m Popeye the sailor man— over and over again, like a record needle skipping, while eating Alpha Bits or Apple Jacks or Cap’n Crunch and chewing along in the same rhythm. I don’t understand why I’m not allowed to do tons of stuff other kids do like choose my own clothes or get haircuts I like or have a pet turtle, but I get all these cereals other kids aren’t allowed to eat. Like my friend Evee who lives upstairs in our building is only allowed Grape Nuts, which she let me taste once and it was exactly like the time I put a bunch of pebbles in my mouth because I heard that Boy Scouts do that when they’re thirsty but their canteen is empty. I also want a canteen. My brother has one and says it’s useless because we live in an apartment with five bathrooms and a kitchen so you can turn on a faucet every few feet to get water, but if I had a canteen I’d use it when Leni takes me to the park— if I had a canteen I’d use it in case I got thirsty just going downstairs to get the mail. I know I’m lucky not to be forced to eat Grape Nuts and to get whatever cereals I want, especially Cap’n Crunch, but it’s not enough to keep me from thinking about suicide.

So this night, on vacation in Acapulco, while I’m playing hide-and-seek with my brother after dinner without permission, I suddenly hear my mother scream my brother’s name, “Jimmy!” and my brother immediately straightens like my GI Joe when I make him salute, and shouts “Yes!” My mother yells again, “Have you seen that sister of yours?!” and I see my brother’s head darting up and down and side to side to uncover where our mother’s voice is coming from. From my platform perch I see her smoke first, a gray cloud behind the tall hedges moving quickly forward like the smoke from a train chimney. I look over the railing— on tiptoes my head clears it— to the tennis court below, testing my arm strength by gripping the rail and pushing myself up gymnast-style until my elbows lock and I’m high enough to look straight down to the court below. If I want, I can get myself over it by leaning forward. If I want, I can definitely fall all the way down. Of course I know I won’t bounce like a tennis ball, or even like a racquet ricochets when the older kids get mad during their tennis lessons. I mean, obviously I know I’ll die, it will be over fast, like a slap, probably upon impact if I land headfirst like I’m not supposed to on the trampoline at school. I see my body lying there after, a jumble of me, blood oozing out slowly— like from squeezing a ketchup packet when the hole is too small— and puddling all around me as my mother, still smoking, looks down at me while stepping backwards so she doesn’t get blood on her shoes. Will my mother touch me, I wonder, to check if I have any life left in me? I decide she won’t. Instead, she’ll have my father lift me up and carry me… but to where? Where will my body be kept until the vacation is over and we go home to New York for my funeral?

That I don’t jump this night matters in two ways. The obvious way, but also something else: I think something that night I can never unthink. I don’t know if, during childhood, I think about dying more than other kids growing up in unhappy families, but after this night I retain the total and complete power to control one perfect thing in my life.

Recent Work

The First Time I Consider Ending My Life I Am Four – Room Magazine

The Day After Wikipedia Still Lists Her in Present Tense – The Southampton Review

The Name Dropper – The Maine Review

My Earliest Self is a Boy… – Electric Lit

T – The Rumpus

Denny and Me – Passengers Journal

Small-Town Nonsense – The East Hampton Star

A Conversation with Morgan Talty – The Rumpus

My Avatar (aka afab perpetrates heteronormative relationship) – Holy Gossip

What Goes Around – EAST Magazine

The Liar – The Normal School

I Drew a House – The Rumpus

More

HYBRID – Columbia Journal

Blended Family – The Southampton Review

There are No Baked Potato Chips in Palm Beach – Dash Literary Journal

Last Night I Dreamed My Mother Was Carl Reiner and I Was Sad She Died – Bangalore Review

Time Will Tell – The Fiddlehead (Excerpted from Winter 2023 Print Journal)

Parallel Family – Harvard Review

Finding Barbie’s Shoes – Streetlight Magazine

Deformed – RFD Magazine

#2486 – The Southampton Review

On Drinking – Stonecoast Review

My Last Dress – The Sun Magazine

Reviews and Interviews

Misperceptions, Assumptions, and Slurs: Jackie Domenus's No Offense – The Rumpus

A Conversation with Morgan Talty – The Rumpus

Naming Stars: An Interview with Andrés N. Ordorica – The Massachusetts Review

Interview by J Brooke of Hotel Cuba’s author Aaron Hamburger – Streetlight Magazine

J Brooke’s Reading Recommendations – The Fiddlehead

Two New Series Bravely Lose The Labels – Incluvie Film Review

Review of Melissa Febos’ Girlhood – Glint Journal

Review of Susan Conley’s Landslide – Streetlight Magazine

Interview with Massachusetts Review

Interview with Stonecoast Review

About

Awards

Columbia Journal: First Place Winner, 2020 Nonfiction Award for autobiographical essay “HYBRID”

Beyond Words Literary Magazine: Winner, 2020 Dream Challenge “Kaden has Covid”

The Maine Review: Hon. Mention, 2021 Embody Award for essay “HIDEOUS”

Sunspot Lit: Finalist, 2020 Inception Contest Flash Fiction “Before and After”

Streetlight Magazine: Hon. Mention, 2020 Essay Contest “Finding Barbie’s Shoes”

Gival Press: Finalist, Oscar Wilde Award 2021 for poem “Self-Portrait at Age 9 as Albert Cashier”

Craft Literary: Hon. Mention, 2021 Flash Fiction Award

North American Review: Finalist, 2020 Kurt Vonnegut Prize